LST 920 PROJECT: Charlie Botula's Long, Slow Target!

LST 920 Project – An Introduction

December 1945

The cab pulled up and stopped in front of the house. A Navy officer got out and looked up at my mom and me. “There’s your dad, Michael,” she said. I remember running toward him at full speed, screaming at the top of my lungs and jumping into his arms. My dad was home. The war was finally over, but the story was just beginning.

August 2003

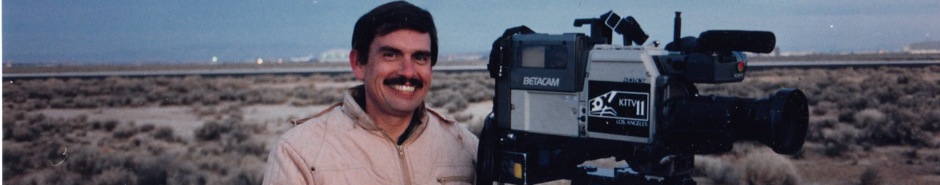

As I approached my retirement date, I began to sort through my father’s personal files, which had been in storage for nearly half a century. There were cartons of personal documents, letters, photos, and other artifacts from the mid-1940s, when he served as an officer on a US Navy Landing Ship – the LST 920 in Europe and the Pacific during World War II. Telling the story of Lt.(jg) Charles Botula, Jr., has been a labor of love for me and it is intended as a tribute to those American men and women who were part of The Greatest Generation.

Unlike many other WW2 veterans, my dad freely shared his stories of his wartime naval service with his family and friends. Many of that same generation if they survived the war, put their uniforms away after coming home and tried to pick up their lives where they left off on December 7, 1941. Charlie Botula did just that. He came back to the states to his wife and two sons – the youngest having been born while he was in the South Pacific, and came back to the small town on Long Island where he had lived; and returned to the job he had held before he was commissioned. My father bought a home in Riverhead, NY where my brother Charles and I grew up. Our mother, Mary, or “Skip” Botula as my dad and all of her friends called eventually went back to her nursing career until she died of cancer in 1961. My father died shortly afterwards in 1965, never knowing the full story of the life-changing event in his navy career – the U boat attack on his ship in the Bristol Channel off the coast of England in August of 1944. He had long-intended to sort through his wartime experiences and write on the subject himself, but, life had a knack of keeping his intentions at bay. He had left that to me, and many years would pass before I could focus on his wartime story.

It was in 2003 that I posted an email message on a special interest internet site devoted to World War Two’s American landing ship fleet. My father, Lt. Charles Botula served as Executive Officer aboard the LST 920 in the war. I would like to contact any other crew members who served with him, I wrote. To my surprise, I received a quick response. Lt. Don Reed, now of Redwood City, California, was the communications officer aboard the LST 920 from its commissioning in June 1944 until decommissioning in September 1946. Mr. Reed shared with me his experiences, photos, articles he had written and the research he has done over the years on the ship and crew. Another crew member, Seaman Larry Biggio had created a website devoted to the LST 920 his shipmates aboard her. They, in turn led me to Ensign Don Joost, Engineering Officer aboard the 920’s ill-fated sister ship, the LST 921. All three men eagerly shared with me their recollections, research, internet files and other resources to me in my new role as “keeper of the flame.”

The LST 920 Project is a collection of related stories, but, to me, the lead story is the attack by Kriegsmarine U boat 667 on the convoy that the LST 920 and the LST 921 were sailing in on August 14, 1944. So let us begin with that. There is also an ever-growing photo gallery with pictures that were processed in the clandestine on board dark room, and a first time profile of the 920’s Captain – Harry Niel Schultz. And last, but definitely not least, for the first time you will hear the story of the attacking German U boat and its crew that went to the bottom of the English Channel two weeks after the attack in the Bristol Channel. Enjoy!

©2019

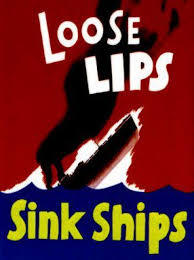

LST 920's Photo Shop or "Loose Lips......Are Everywhere!"

The US Navy imposed the utmost secrecy on its wartime operations. The LST 920 began its career shrouded in secrecy from the moment of its commissioning on June 17, 1944. First photos of it at sea show that it was painted in the Pacific Theater camouflage coloration. The D-Day invasion of Normandy had already taken place and the Allies were rolling the Nazi juggernaut back toward the Rhine. And while it's mission was not revealed to the crew, it was assumed by most that the ship would be headed to the Pacific and the war against the Japanese. But, almost overnight the LST 920 returned to port for a complete change of color scheme-the dull gray of the European Theater of Operations. And indeed, after it's shakedown cruise in July and August 1944, LST 921 and her sister ship LST 921 steamed to Philadelphia to pick up a top secret cargo before joining the one-thousand ship convoy from the US to England.

Letters between the crew and back home were censored, and photographs were strictly forbidden. Crew members with cameras faced a court martial. And, yet a clandestine darkroom aboard ship was a bee hive of activity all during the ship's time in wartime service. Surviving crew members of the LST 920 or their families were eager to share their wartime photos, some of which were even captured from the enemy. The LST 920's wartime Photo Gallery is a work in progress, but it will help to answer the question that is ever on the minds of families of those who served, What did you do in the War, Daddy?

LST 920 Project: A Work in Progress

Background

In 2003, I began to sort through my father’s personal files. There were cartons of personal papers, photos, and other artifacts from the mid-1940s, when he served as an officer in the US Navy in Europe and the Pacific during World War 2. It has been a labor of love for me and a tribute to a man who was part of The Greatest Generation.

Dad shared freely his stories of wartime naval service with his family, unlike many other WW2 veterans who finished their jobs, came back home and resumed their lives, keeping their wartime experiences to themselves.

Two of dad’s shipmates have made tremendous contributions to this effort. Lt. Don Reed, now of Redwood City, California, was the communications officer aboard the LST 920 from its commissioning in June 1944 until decommissioning in September 1946. He became a devoted historian following the war continuing to write about the ship and its crew. Mr. Reed was shared with me his experiences, photos, articles he had written and the research he has done over the years on the amphibious navy and the LST 920. Another crew member, Seaman Larry Biggio created a website devoted to the LST 920 and its crew members. In 2011, Mr. Biggio retired and passed along his research, internet files and resources to me in my new role as “keeper of the flame.”

The LST 920 Project is made up of a collection of related stories. We'll be adding to them regularly as time goes by - Mike Botula.

©2015

The Enemy Below - U 667

“LOST MUSKET DIARY” Wednesday December 3, 2014

Rainy 61°F/16°C in Rancho Santa Margarita

Buongiorno,

[Editor's note: This article was originally published on my blog bymikebotula.blogspot.com in December 2014, prior to the 73rd anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Even the identity of the U boat that attacked my dad's convoy back in 1944 was unknown at the time. Action reports of the time only refer to the attacker as "enemy submarine." Neither the identity of U667 nor its fate were known until this project got underway in 2003. Lt. Botula and Captain Schultz both passed away without ever knowing their enemy].

As we count down to the 73rd anniversary of that “Day of Infamy,” as President Franklin D. Roosevelt called it, I’m still digging into another story about World War 2, the U boat attack on my father’s ship in the Bristol Channel off the coast of Britain, later in the war than December 7th 1941. His high seas adventure took place on a sunny summer afternoon in August 1944.

My father, Lieutenant (jg) Charles Botula, Jr, never had a chance to meet Admiral Karl Dönitz, and to my knowledge, he had never heard of Karl-Heinze Lange either. However, he certainly had a chance to witness their handiwork. The World War II “Battle of the Atlantic” got very up close and personal for my dad and the crew of his ship, the LST 920. On that long ago afternoon, it was a few minutes before 5 p.m. and the crew was getting ready for chow, when the convoy they were sailing in - EBC-72 - came under attack by the German U Boat 667, commanded by Karl-Heinze Lange. A torpedo had struck the 920’s sister ship, LST 921, breaking it in two. Then, as my father watched from the bridge, a torpedo trail headed relentlessly toward his ship, the 920. It would have struck dead amidships had it not been for the British Corvette that was escorting the convoy from Milford Haven, Wales to Falmouth, England. The Brit, LCI(L)99 took the full brunt of the torpedo’s wrath, blowing it out of the water just a short distance from its intended target, the 920.

The attack was followed by a courageous move by the 920’s skipper, Lt. Harry N. Schultz, who, in a violation of the hard and fast order to stay with the convoy, ordered his ship to come about to pick up any survivors from the LST 921 and the LCI(L)99. In Schultz’s mind, an ancient law of the sea trumped any contemporary rule for navigating a war zone. While the enemy sub stayed in the area, looking for an opportunity to resume the attack, the rescue effort continued into the night. As survivors were pulled from the chilly waters of the Bristol Channel, the sub stayed just out of the range of the new three inch gun Captain Lange thought the LST 920 was carrying. Lange was wrong. The 920 was equipped only with 40 millimeter weapons. Another bit of luck for the rescuers. The next day, it left the area and sailed to its home base in France to report a successful mission to Admiral Dönitz. U 667 never reached its home port. Neither my father, nor any member of his crew knew who had attacked them or what fate had in store for the enemy.

A clearer picture of what happened on August 14, 1944, comes into focus if you know a little bit more about Admiral Dönitz and his philosophy of waging war. Simply stated, it was to destroy completely the enemy’s ability to wage war, a practice by great commanders past, present and future from Alexander the Great to Julius Caesar to Genghis Khan to Napoleon Bonaparte, to American Civil War Generals U.S. Grant and, especially William Tecumseh Sherman. Karl Dönitz learned the craft of submarine warfare during World War I, when Germany terrorized the Allied shipping lanes and initiated its own downfall with the torpedoing of the Lusitania, bringing the US into the war.

Being an island nation had kept invaders out of Britain from the time of William the Conqueror in 1066 right up until the eve of World War 2. As Germany shook off the shackles of The Versailles Treaty, Adolf Hitler and his generals began to plan for an invasion of Britain. From the rubble of the First World War Germany had built a massive military machine with its Luftwaffe, Wehrmacht and Kriegsmarine. Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz’ purview would be the Navy and its fleet of unterseebooten, the dreaded U boats. When WW2 began in 1939, so did the Battle of the Atlantic, the longest naval struggle in history from outbreak to Germany’s surrender in 1945. The Allies lost 3,500 merchant ships and warships. The Germans lost 783 of its 1153 U-boats. By the time that LSTs 921, 920, AND LCI(L)99 met up on August 14, 1944 with U 667, the war was in its final year and the Germans had already lost the Battle of the Atlantic.

When I first heard the story about this U boat attack, it was little more than a wartime anecdote that my dad told over the Sunday dinner table as I grew up. Dad was proud of his wartime Navy service and he loved to regale his two young sons with his “war stories.” My brother and I grew up listening to them. The whole story played out over just a few days’ time in late 1944, but it took years for me to find out all the facts. Apart from the names of his own shipmates dad was in no position to learn any of the details relating to the other ships involved or their crews. It was not until after I retired that I started treating this story as I had done so many other stories that I covered during my long career as a journalist. And as I carried out my research and each new fact came to light, I was on to one hell of a war story.

I have distant memories of a June day in 1944, when my mother took me to Boston by train from New York. My father had already been away from home for almost a year by then. I was about four and we were in Massachusetts to attend the commissioning of my dad’s brand new ship. By the time the new crew took its new ship out on its shakedown cruise, the LST 920 was sporting a brand new camouflage paint job and was getting ready to head to the Pacific. But orders changed at the last minute and it headed to Philadelphia to pick up a “secret cargo.” The 920’s sister ship, LST 921 received the same orders and the two new ships headed to Philadelphia toward the end of July to pick up their mysterious cargo. Both received new paint jobs, literally overnight, along with new orders – to join a one-thousand-ship-convoy off Nova Scotia and head across the North Atlantic. At about the same time, July 22, 1944, U 667 set sail from its base at St. Nazaire, France with its new commander, Kapitan Leutnant Karl-Heinze Lange in search of allied shipping. Along with its new skipper, U 667 had been outfitted with the new Schnorkel, the underwater breathing device that allowed U boats to remain under water for the duration of their missions without having to surface and be vulnerable to Allied air attacks.

By August 9, 1944, Convoy HXM 301 with the LST’s 920 and 921 had successfully crossed the Atlantic and arrived in Liverpool, England. As the long journey ended for them, their nemesis, the U 667 was already drawing blood. The day before, on August 8th, U 667’s new skipper had scored his first kills, a US Liberty ship, the SS Ezra Weston and a Canadian escort vessel, HMCS Regina. The Ezra Weston took the first torpedo, and as the Regina came to the stricken ship’s aid, it too was torpedoed. One officer and 27 men aboard the Regina were killed; the ship’s commander and 65 crewmen were saved, although two of the survivors died before they could reach a hospital. All 71 crewmen aboard the Ezra Weston survived the attack. Now, on the afternoon of August 14, 1944 the two LSTs were en route from Milford Haven, Wales to Falmouth, England toward their ultimate destination – Omaha Beach in Normandy. U 667 spotted their convoy in the Bristol Channel.

U 667 was one of 1153 German submarines commissioned in World War II. It was a Class 7C submarine which first saw action in 1942. Its first Captain, Heinrich Schroteler was in command for four missions. While U 667 is credited with shooting down an RAF bomber, it did not score any “kills” against Allied shipping, although Schroteler did sink a British minesweeper and a Norwegian tanker in the waning days of the war in 1945 aboard the U 1023. His successor on U667, Captain Lange, had better luck, scoring four kills within two weeks in August 1944. The Weston and Regina on August 8th and the LST 921 and LCI(L)99 on August 14th. But, as Lange and U 667 steamed away from the site of their latest victory, neither the Captain or his crew could know that there luck was about to change.

In all of the research I did for this story, the archives of the Navies, US and German, revealed only that U 667 struck a mine on or about August 25th on the way back to a hero’s welcome at its home base at La Rochelle, France. I found the answer on a specialty internet site uboat.net, which is devoted to the archives of the Kriegsmarine and especially it’s Unterseebooten.

According to the archives, the RAF had carried out a series of aerial minelaying missions off the coast of France right about the time that U 667 was carrying out its last deadly mission. Minelaying had been carried out by both sides in the Bay of Biscay. The Germans to keep the Allies away, and the Allies to keep the Germans bottled up in their home ports or to snag them on the way home. In a report on the August 1944 minelaying sweep, the map coordinates of the area sown match the location where the wreckage of the U 667 was finally located and examined by diving crews. The loss of the U 667 was recorded by the Kriegsmarine when it missed a scheduled radio check-in on August 25th. By then, Admiral Dönitz and his high command had begun to assume that if a scheduled check-in was missed by one of his U-boats, it meant that the sub had been lost. In fact, U 667 did become a war grave less than two weeks after it’s most recent victory. Ironically, none of the survivors of its last wartime attack ever knew what happened to the submarine that had so impacted their lives.

Ciao, MikeBo

Casualty Lists From 14 August 1944 and Sinking of U 667

Lt. Charles Botula’s Memorial Day Story

We have a shared responsibility to look directly into the eye of history and ask what we must do differently to curb such suffering again… President Barack Obama at Hiroshima

When I was a little boy, Memorial Day was still called Decoration Day and it fell on May 30th. My mom told me it was a memorial event that started at the end of the Civil War, because that’s when Americans would pay tribute to the fallen who wore both blue and grey by decorating their graves with flowers. The observance actually began with former slaves celebrating the Emancipation Proclamation by decorating the wartime graves of African-Americans who fought for their freedom from slavery. Decoration Day quickly became a memorial day honoring Americans who fell in all of our country’s wars. After World War I, we honored the fallen of The Great War on each November 11th. For many years, November was Armistice Day, and on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of the year there was a moment of silence to commemorate the end of The War to End All Wars. In 1968 Congress revamped our national holidays, combining these hallowed days into a pair of three-day weekends. Decoration Day is now Memorial Day and Armistice Day is now Veterans Day. Today we will again honor those who fought and died for their country. But, as the years pass, the real meaning of both days is sometimes lost in the holiday atmosphere that accompanies any long weekend.

When my father returned from his US Navy service in World War II, he told my brother and I a story that I retell to my own son and daughter, and now my grandchildren as every new Memorial Day approaches. It begins with a few terse lines from the LST 920’s Ship’s Log:

LST 920 Ship’s Log: Monday 14 August 1944

1654 hours: First hit on LST 921, directly astern of us. Presumably by torpedo.

1654 hours: General Quarters sounded

1656 hours: LCI #99 (British) hit by torpedo presumably

1657 hours: All stations manned and ready; approximate position…50°54’ North, 4°45’ West

1657 hours: Relieved on conn by Captain Schultz and went to GQ station

Ensign John J. Waters, Officer of the Deck

My dad served as Executive Officer aboard the LST 920 during World War 2. His ship survived a deadly U boat attack on his convoy that sank a British escort ship and heavily damaged LST 921, the sister ship to the LST 920. The loss of life was heavy. The British ship, LCI(L)99 was literally blown out of the water. LST 921 was torn in two, with the aft section sinking with half the crew. I’ve shared this story before. In fact, I’ve written a book about it, LST 920: Charlie Botula’s Long, Slow Target! My dad, Lt. (jg) Charles Botula, Jr. died in 1965 without ever knowing the full story about the afternoon of August 14th, 1944 off the west coast of England. It’s taken me years to research it. Neither my Dad nor his Captain – Harry N. Schultz ever knew which enemy submarine attacked them or what happened to that U boat after the LST 921 and HMS LCI(L)99 were torpedoed. Most of the survivors of that terrible afternoon have also faded from our midst, but their story is well worth the retelling. For in the retelling, we can pay them a long overdue honor.

Monday, 14 August 1944 -16:54 hrs. - USS LST 920, commanded by Lieutenant Harry N. Schultz and USS LST 921, under the command of Lieutenant John Werner Enge were underway in convoy EBC 72 from Milford Haven, Wales to Falmouth, England. They were suddenly attacked by the German submarine U667, under the command of Kapitӓnleutnant Karl-Heinze Lange. LST 921 was hit by the first torpedo and broke in two with the aft section sinking minutes later. Some survivors scampered to safety on the bow section. Others went overboard into the chilly water. When the aft section sank, it took half of the ship’s crew to the bottom. General Quarters was sounded on the LST 920 and Captain Schultz came to the bridge.

Seeing survivors in the water, Schultz ordered his radioman, Seaman Fred Benck to send a request for permission to turn his ship around to pick up survivors. Permission was denied and the 920 was ordered to proceed to Falmouth. Years later, Benck told me what happened next. In about two minutes he came in the radio room and said, Benck send that message again! This time he waited for the answer which was the same, DO NOT BREAK CONVOY! H. N. Schultz then used these words: TO HELL WITH HIM! And we pulled out of convoy to turn back and pick up survivors! A message came from the Commander of the convoy to get back in formation. This message was never answered.

As my father watched from the bridge of the LST 920, he spotted a torpedo coming straight at him. Just then, a British escort vessel, LCI(L)99 came alongside, took the full brunt of the torpedo and was blown out of the water. The 920 came about and Schultz ordered two small boats into the water with Ensign John Waters in one and Ensign Harold Willcox in the other, along with nine other sailors to rescue survivors. Willcox tied a line around his waist and jumped into the water numerous times to help pull survivors aboard. In his After Action Report, Captain Schultz singled out Waters and Willcox and the nine seamen for outstanding performance during the action. In all, 48 survivors were rescued and brought aboard the LST 920. Seaman Joe Wallace tells this part of the story, I remember one of the 921 crew members coming up to the bridge all wet and oily. I gave him my locker keys and location, and he showered and put on some clean dry clothes. By this time it was dark. We gathered the survivors and were on our way to Falmouth. There, I had the task of counting the departing survivors - 42 walking and 6 stretcher cases.

A number of other survivors from the 921 as well as the LCI(L) 99 were rescued by a British ship that joined in the rescue operation. All told, about 65 survivors were picked up, but fully half of the LST 921’s complement of 107 officers and crew had been lost. Years would pass before a dusty and forgotten archive* would reveal the names of the sailors – Americans, British and German who lost their lives on that August afternoon more than seventy years ago. And so, each year on Memorial Day, I would like us to remember:

Baker, Thomas A., USNR Seaman First Class

Banit, Roman J., USNR Seaman Second Class

Bennett, Frederick W., USNR Seaman First Class

Bent, Eugene E., USNR Seaman First Class

Clements, Charles M., USNR Seaman First Class

Dove, Raleigh J., USNR Seaman Second Class

Enge, John Werner, USNR Lieutenant (Captain, survived)

Feeney, Lawrence E., USNR Fireman Second Class

Fitton, Edward Joseph, USNR Seaman Second Class

Freely, James Joseph, USNR Boatswain's Mate 1st Class

Furino, Louis A., USNR Coxswain

Guthrie, Edward J., USNR Ensign

Guziak, Walter V., USNR Seaman Second Class

Hoak, William K., USNR Gunner's Mate Third Class

Jerzewski, Chester R., USNR Seaman Second Class

Jones, Oscar R., USNR Coxswain

Kozlik, John H., USNR Seaman First Class

Lowe, Samuel M., USNR Seaman Second Class

Micheline, Carmine A., USNR Seaman Second Class

Mindlin, Daniel, USNR Ensign

Monaco, Robert Chester, USNR Radioman Second Class

Moore, Charles H., USNR Seaman Second Class

Mulholland, William P., USNR Seaman Second Class

Newberry, Clyde, USNR Seaman Second Class

Pizon, John J., USNR Seaman First Class

Potasky, Joseph E., USNR Seaman First Class

Progy, Henry, USNR Motor Mach Mate 3rd Class

Richard, Donald James, USNR Gunner's Mate 3rd Class

Siring, Ronald John, USNR Ship's Cook Third Class

Smith, Kenneth J., USN Boatswain's Mate 2nd Class

Smith, Lee I., USNR Seaman Second Class

Smith, Ray R., USNR Seaman First Class

Sprague, Herbert K., USNR Seaman Second Class

Suazoe, Ray M., USNR Seaman Second Class

Totulis, Albert G., USN Gunner's Mate 3rd Class

Trachsel, Ernest W., USNR Seaman Second Class

Van Why, Henry, USNR Seaman Second Class

Verity, Edward C., USNR Seaman Second Class

Vitense, Glenn, USNR Seaman First Class

Widmer, Richard C., USNR Seaman Second Class

Yavornitzky, Andrew J., USNR Shipfitter Second Class

The British escort vessel – LCI(L) 99 was a much smaller ship than the wounded LST 921. It was about 150 feet long compared to the LST’s 328 feet. And, instead of a ship’s complement of 110 officers and crew, LCI(L) 99’s casualty list shows a crew of eight – two officers and six enlisted men, including the 19 year-old ship’s cook, Able Seaman William Todd. Todd’s great-niece, Gillian Whittle told me in an email, Bill as he was known was only 19 when he died, and he came from Chorley, Lancashire, England. I imagine he was called up when he turned 18, I don't know his birthday. He was acting able seaman and he was actually the ships cook. We as a family are very proud of him and I go to Kent, England when I can to lay flowers at the naval memorial. I am afraid I don't know much else about my Uncle, but I have his medals and I had the privilege of wearing them proudly on remembrance parade for him one year and we keep his memory going.

Also aboard the Escort Ship LCI(L) 99 on that deadly August 14, 1944 were:

Lt. Commander Arthur John Francis Patrick Reynolds, RN, Age 24

Sub-lieutenant Douglas Edwin Swatridge, RNVR, Age 25

Leading Seaman Gordon Henry Astor House, RN, Age 21

Able Seaman James Quine, RN, Age 21

Able Seaman Francis Ernest Dennis Shacklock, RN, Age 19

Ordinary Seaman John Shields, RN, Age unknown

Ordinary Seaman Donald Maurice Thompson, RN, Age 20

Able Seaman William Todd, RN, Age 19

There is an important postscript to this story. The attacking submarine, U 667, had sunk four ships including the LST 921 and LCI (99), the Liberty Ship SS Ezra Weston and HMS Regina on what turned out to be its most successful cruise, as well as an RAF bomber on a previous mission. But as it headed back to its base and a hero’s welcome, its jubilant crewmen could not know that their luck was about to change. In all of the research I did for this story, the US Navy and German Kriegsmarine archives revealed only that U 667 struck a mine on or about August 25th on the way back to its home base. But, as I researched further, I found the answer on a specialty internet site: uboat.net, which is devoted to the archives of the Kriegsmarine and its unterseebooten. According to the archives, the RAF had carried out a series of aerial mine-laying missions off the coast of France in an area code-named Cinnamon right after the U 667 left port on its final cruise. The RAF dropped mines into the U 667’s inbound route back to base. An RAF report that I read showed that the coordinates of that August 1944 mine-laying sweep matches the location where the U 667 was finally found and examined by diving crews. The loss of the U 667 was recorded by the Kriegsmarine after it missed a scheduled radio check-in on August 25th. When U 667 failed to check in, Admiral Karl Dönitz’ high command assumed that the sub had been lost. Ironically, neither my father nor his Captain, Harry Schultz, nor any of the survivors from LST 921 ever knew what happened to the submarine that attacked them. The exploding mine sent U 667 to the bottom of the Bay of Biscay, where it remains with its entire crew of 45. The wreckage is now war grave. Along with the U 667’s Kapitӓnleutnant Karl-Heinze Lange, the identities of the other sailors in his crew are listed from the roster of all the sailors who served aboard her. They are:

|

Name |

Rank (In German) |

Age |

|

Lange, Karl-Heinze |

Kapitӓnleutnant |

26 |

|

Bauch, Walter |

Omasch |

30 |

|

Bensel, Rolf-Rudiger |

Olt.z.S. |

21 |

|

Borowsky, Helmut |

MaschMt |

23 |

|

Brübach, Friedrich |

MtrOGfr |

20 |

|

Brunk, Kurt |

MaschOFfr |

21 |

|

Drewes, Gustav |

MaschMt |

23 |

|

Eder, Franz |

MaschOGfr |

21 |

|

Ederer, Hans |

OfkMt |

24 |

|

Ehrenfeld, Kurt |

OfkMt |

25 |

|

Erasimus, Johann |

MaschOGfr |

20 |

|

Faust, Erich |

Olt.z.S |

23 |

|

Fickert, Wilhelm |

MtrOGfr |

23 |

|

Figlon, Herbert |

MechOGfr |

22 |

|

Flach, Hans |

OsanMt |

23 |

|

Grimm, Kurt |

MaschOGfr |

20 |

|

Hagelloch, Hans-Georg |

OLt.ing.d.R |

23 |

|

Hahl, Adam |

MaschOGfr |

21 |

|

Hantel, Artur |

MtrOGfr |

22 |

|

Hochstetter, Wilhelm |

OMaschMt |

23 |

|

Holle, Oswald |

MaschOGfr |

20 |

|

Kabs, Helmut |

MaschOGfr |

21 |

|

Krӧller, Helmut |

Olt.z.S |

23 |

|

Laschke, Kurt |

MaschMt |

21 |

|

Leisler-Klep, Jürgen |

Lt.z.S |

n/a |

|

Matthias, Heinz-Karl |

OMaschMt |

25 |

|

Mӓurer, Ludwig |

FkOGfr |

21 |

|

Mittler, Arnold |

MaschOGfr |

21 |

|

Mrziglod, Heinrich |

BtsMt |

22 |

|

Oehler, August |

MtrHGfr |

38 |

|

Proske, Walter |

MtrOGfr |

21 |

|

Reiβach, Werner |

StOStrm |

30 |

|

Reitor, Emil |

MechOGfr |

21 |

|

Richter, Georg |

OMasch |

32 |

|

Richter, Helmut |

OMechMt |

24 |

|

Sauer, Helmut |

MtrOGfr |

21 |

|

Schӓfer, Richard |

MaschOGfr |

19 |

|

Scheit, Reinhold |

ObstMt |

27 |

|

Schӧmetzler, Rudolf |

MaschOGfr |

20 |

|

Schrӧder, Gerhard |

MtrOGfr |

21 |

|

Schrӧder, Günther |

Olt.z.S |

30 |

|

Schulz, Kurt |

OMaschMt |

24 |

|

Seeliger, Willi |

MtrOGfr |

20 |

|

Senden, Wilhelm |

MtrOGfr |

21 |

|

Steigerwald, Wilhelm |

FkOGfr |

20 |

|

Warmbold, Adolf |

MtrOGfr |

23 |

|

Weiβ, Rudolf |

MaschOGfr |

21 |

|

Witzel, Hans |

BtsMt |

23 |

|

|

|

|

It’s fitting that we remember all who perished.

Eternal Father, strong to save,

Whose arm hath bound the restless wave,

Who bidd'st the mighty ocean deep

Its own appointed limits keep;

Oh, hear us when we cry to Thee,

For those in peril on the sea!

-Navy Hymn

*LST 921; LCI(L)99; U 667 casualty lists via US Navy Archives, Royal Navy and Uboat.net.

U 667 Wrecksite Photos from L'Expedition Scyllias - www.scyllias.fr

© By Mike Botula 2018

Final Resting Place of U 667 - En Route to La Pallice, France

PHOTO GALLERY

U 667's Attack On Convoy EBC-72. Monday, 14 August 1944

LST 921: The Final Muster

Monday, 14 August 1944 -16:54 hrs. - USS LST’s 920, commanded by Lieutenant Harry N. Schultz and USS LST 921, under the command of Lieutenant John Werner Enge were underway in convoy EBC 72 from Milford Haven, Wales to Falmouth, England when they were attacked by the German submarine U667, under the command of Kapitӓnleutnant Karl-Heinze Lange. LST 921 was hit by the first torpedo and broke in two with the aft section sinking a few minutes later, taking half of the ship’s crew to the bottom. As my father watched from the bridge of the LST 920, he spotted a torpedo wake coming straight at him. Just then, a British escort vessel, LCI (99) came alongside and took the full brunt of the torpedo and was blown out of the water. General Quarters was sounded and the LST 920’s Captain, Harry N. Schultz came to the bridge. Seeing that there were survivors from the LST 921 in the water, he ordered his radioman, Seaman Fred Benck to send a message requesting permission to turn the 920 around to pick up survivors. Schultz’ request was denied and he was ordered to proceed to Falmouth. Years later, Benck recalled what happened next. “In about two minutes he came in the radio room and said, Benck send that message again! This time he waited for the answer which was the same words, DO NOT BREAK CONVOY! H. N. Schultz then used these words: TO HELL WITH HIM! And we pulled out of convoy to turn back and pick up survivors! A message came from the Commander of the convoy to get back in formation. This message was never answered.”

As the 920 came about, Schultz ordered two small boats into the water with Ensign John Waters in one and Ensign Harold Willcox in the other, along with nine other sailors to rescue survivors from the British ship and the LST 921. Willcox tied a line around his waist and jumped into the water numerous times to help pull survivors aboard. In his After Action Report, Captain Schultz singled out Waters and Willcox and the nine seamen for outstanding performance during the action. In all, 48 survivors were rescued and brought aboard the LST 920. Seaman Joe Wallace tells this part of the story. “I remember one of the 921 crew members coming up to the bridge all wet and oily. I gave him my locker keys and location, and he showered and put on some clean dry clothes. By this time it was dark. We gathered the survivors and were on our way to Falmouth. There, I had the task of counting the departing survivors - 42 walking and 6 stretcher cases.”

A number of other survivors from the 921 as well as the LCI (99) were rescued by a British ship that joined in the rescue operation. All told, about 65 survivors were picked up, but fully half of the LST 921’s complement of 107 officers and crew had been lost.

Postscript:

The Skipper of the LST 921, Lieutenant John Werner Enge, survived the attack, as did his Engineering Officer, Ensign Don Joost and Machinist’s Mate John Abrams. Joost and Abrams related their memories of that fateful day. Joost had just left the engine room to return to his quarters just before dinner. Abrams was in the engine room along with a shipmate when the U 667’s torpedo struck near the stern. Realizing the stern would sink, Joost helped other crewmen to safety up forward before the after section broke off and sank. Abrams helped another crew member swim up an escape tube from the flooded engine room. Another 921 crew member who survived was Fireman First Class Gerald Earl Hendrixson, who was rescued by his brother Harold Hendrixson’s shipmates from the rescuing ship LST 920. Anxious hours for the Hendrixson brothers, followed by a jubilant reunion on board LST 920. Joost was picked up by the British and was hospitalized at a location away from the crewmembers rescued by the 920, so, he was briefly listed as Missing in Action. Joost was decorated for valor in the action. Enge returned to his native Alaska after the war.

Another important postscript to this story:

The attacking submarine, U 667, had sunk four ships including the LST 921 and LCI (99) on what turned out to be its most successful cruise. But as it headed back to its base and a hero’s welcome, its jubilant crew could not know that their luck was about to change. In all of the research I did for this story, the US Navy and German Kriegsmarine archives revealed only that U 667 struck a mine on or about August 25thon the way back to at its home base at La Rochelle, France. Digging further, I found the answer on a specialty internet site: uboat.net, which is devoted to the archives of the Kriegsmarine and its unterseebooten.

According to the archives, the RAF had carried out a series of aerial minelaying missions off the coast of France in an area codenamed Cinnamon right after the U 667 left port on its final cruise. The RAF dropped mines onto the U 667’s outbound route. A map of the August 1944 minelaying sweep shows the map coordinates of the area sown match the location where the U 667 was finally located and examined by diving crews. The loss of the U 667 was recorded by the Kriegsmarine when it missed a scheduled radio check-in on August 25th. With that, Admiral Karl Dönitz’ high command assumed that the sub had been lost. The exploding mine sent U 667 to the bottom of the Bay of Biscay, where it remains with its entire crew.

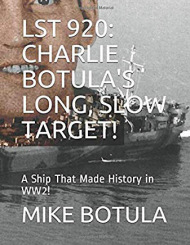

LST 920: Charlie Botula's Long, Slow Target!

A welcome addition to your WW2 history collection from AMAZON BOOKS!

Just go to Books at Amazon.com and enter the title or my name in the SEARCH field. Paperback and Kindle!

DOWN UNDER:

LST 920: Charlie Botula's Long, Slow Target! Now available in Australia from Booktopia.com.au